Pentagon’s Silent Signal: The First Island Chain Strategy

What if the most important move the Pentagon is making in the Indo-Pacific is the one it is not loudly announcing? In recent months, headlines have fixated on carrier deployments, missile tests, and sharp diplomatic exchanges around Taiwan but beneath the noise, a quieter strategy is tightening into place. U.S. defense planners are not drawing new red lines on maps or issuing ultimatums. Instead, they are reinforcing geography itself, turning islands into instruments of deterrence. This is the logic behind the First Island Chain: a strategy that speaks softly, but carries enormous strategic weight.

Consider a simple, almost mundane example. When U.S. and allied forces expand access agreements in the Philippines, upgrade airfields in Japan’s southwest islands, or deepen interoperability with Taiwan’s defenses, none of it looks like a declaration of war. There are no dramatic speeches, no crisis summits. Yet taken together, these moves reshape the battlefield before any shot is fired. They complicate an adversary’s planning, raise the costs of coercion, and quietly signal that control of the Western Pacific will not come easy. This is deterrence by denial in action, winning by making aggression impractical rather than by threatening retaliation.

https://youtu.be/XkvEyrOkaqg?si=tXvZ1H37BdAyjFFy

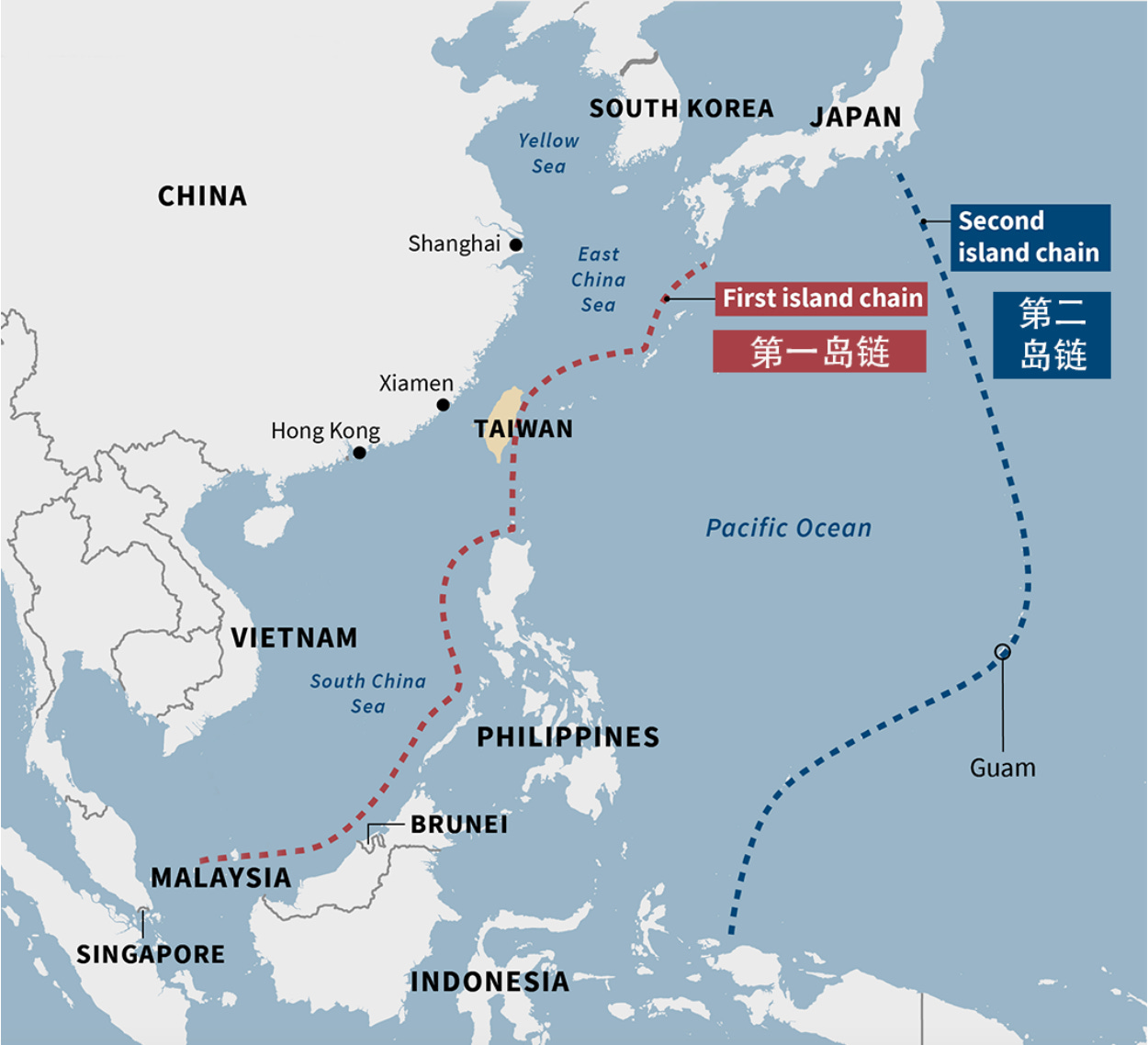

The geography makes this strategy brutally effective. The First Island Chain arcs from Japan through Taiwan and the Philippines toward Southeast Asia, sitting astride the Indo-Pacific’s most vital arteries. More than half of global maritime trade flows through these waters, alongside energy shipments and the sea lanes that underpin the global semiconductor supply chain. The Taiwan Strait, the Bashi Channel, and the South China Sea are not abstract lines on a naval chart; they are economic lifelines. Any disruption here would ripple through markets, factories, and energy grids worldwide. That is precisely why these narrow passages matter so much to both military planners and global investors.

Seen this way, the Pentagon’s Indo-Pacific posture is not about provoking confrontation, but about shaping choices. By reinforcing the First Island Chain, the United States and its partners are betting on a strategy that is intentionally understated yet deeply consequential. The message is clear without being shouted: coercion will be contested, escalation will be costly, and the balance of power in the Western Pacific will be decided less by dramatic gestures than by steady, disciplined preparation. That is the silent signal and it is being sent every day.

Historical Background of the First Island Chain Concept

The First Island Chain did not emerge from today’s headlines or recent tensions, it was born in the anxiety-soaked early years of the Cold War, when Washington was still learning how to contain power without triggering catastrophe. In 1951, as the Korean War raged and communist influence spread across Asia, U.S. strategists began to think less in terms of borders and more in terms of oceans. One influential policymaker captured the logic bluntly at the time: control the seas around Asia, and you control the terms of power projection. The island arc from Japan to Southeast Asia was no longer just geography; it became a defensive wall made of land, sea, and access.

Back then, the concept was simple and unapologetically naval. The United States anchored its strategy on forward bases, carrier strike groups, and chokepoint control to block Soviet and Chinese fleets from breaking into the wider Pacific. Okinawa, Subic Bay, and alliances with Japan and the Philippines were the physical manifestations of this thinking. The objective was straightforward: deny adversaries freedom of movement, keep U.S. forces close to Asia’s rim, and ensure that any attempt to project power eastward would run into a wall of allied presence.

But history did not stand still and neither did the First Island Chain. As technology advanced and threats diversified, the strategy quietly expanded beyond ships and harbors. Today’s version is far more layered and far more subtle. Naval presence still matters, but it is now reinforced by airpower, long-range precision missiles, cyber capabilities, space-based surveillance, and diplomatic alignment. Instead of a single line of defense, the First Island Chain has become a multi-domain web designed to complicate, delay, and deter across every level of conflict.

Its historical impact on the regional balance of power is hard to overstate. During the Cold War, the island chain effectively bottled up Soviet naval ambitions in the Pacific, limiting Moscow’s ability to threaten sea lanes or challenge U.S. dominance beyond Asia’s periphery. After the 1990s, as the Soviet Union collapsed and China’s rise accelerated, the same geographic logic was repurposed. The chain became the backbone of U.S.–Japan security cooperation, the rationale for renewed defense ties with the Philippines, and a critical, if often understated, pillar of U.S.–Taiwan defense relations.https://youtu.be/cEmw6zZlkzU?si=4j4QC78mvO_encaF

What makes the First Island Chain enduring is not nostalgia, but adaptability. It is one of those rare strategic ideas that survives decades because it evolves with power, technology, and politics. From Cold War containment to modern deterrence by denial, it has remained a quiet constant in an otherwise turbulent region, proof that sometimes, the most influential strategies are the ones that never leave the map.

The “Strong Denial Defense” Concept

At the heart of today’s First Island Chain strategy sits a concept that sounds deceptively calm but is anything but passive: “Strong Denial Defense.” This is the Pentagon’s answer to a hard-earned lesson of modern warfare, wars are not only lost on the battlefield, they are often lost in the planning room. If an adversary believes it can achieve its objectives quickly and decisively, the temptation to act grows. Strong Denial Defense is designed to kill that belief before it ever takes root.https://youtu.be/iTN23W9ehOw?si=m0A1G41Z5Xs5B-J3

In simple terms, denial is about slamming the door shut, not threatening what happens after someone breaks in. Under this framework, U.S. and allied forces focus on preventing access and freedom of operation inside the First Island Chain, whether at sea, in the air, or across the electromagnetic and cyber domains. The goal is to make naval incursions fail, air superiority unattainable, and rapid faits accomplis impossible. If an operation cannot succeed in its opening phase, its political and military logic collapses.

This stands in sharp contrast to punishment-based deterrence, which dominated much of Cold War nuclear thinking. Punishment threatens devastating retaliation after aggression occurs, but it also carries severe escalation risks, especially in a nuclear-armed environment. Denial, by comparison, is quieter and more stabilizing. It does not rely on dramatic threats or doomsday scenarios. Instead, it relies on credible, visible capabilities that convince an adversary it simply cannot win, no matter how limited or “controlled” it tries to be.

The strategic objective, then, is psychological as much as military. Strong Denial Defense seeks to shape adversary decision-making at the highest level. By demonstrating that aggression would be ineffective, prohibitively costly, and ultimately unwinnable, the Pentagon aims to narrow the range of options an opponent sees as viable. When leaders look at the map and realize that speed, surprise, and coercion no longer guarantee success, restraint becomes the rational choice.https://indopacificreport.com/philippines-eyes-submarines-from-korea-amid-rising-sea-tensions/

This is why the concept fits so seamlessly with the First Island Chain. Geography already constrains movement; denial capabilities amplify those constraints. Together, they send a clear but understated message: the easiest war to avoid is the one that cannot be won in the first place.

Key Geographic and Strategic Points Along the First Island Chain

If the First Island Chain is the backbone of Indo-Pacific deterrence, then its geography is the muscle and nerve system that makes the strategy work. These are not just dots on a map; they are pressure points where global trade, military movement, and political resolve intersect. Control, access, and influence over these locations shape who moves freely in the Western Pacific and who does not.

Japan sits at the northern anchor of the chain and remains its most heavily fortified node. U.S. bases across Honshu, Kyushu, and especially Okinawa are not Cold War relics; they are forward-positioned enablers of missile defense, airpower, and maritime surveillance. The Ryukyu Islands stretch like a natural fence toward Taiwan, constraining naval maneuver space and giving allied forces the ability to monitor and, if necessary, contest movement through critical sea lanes. From a strategic standpoint, Japan’s geography turns proximity into leverage.

Further south, the Taiwan Strait represents the most sensitive and consequential flashpoint along the entire chain. Taiwan itself is the geographic keystone—its location alone influences the regional balance of power. Whoever can operate freely around Taiwan gains direct access to the Western Pacific; whoever cannot remains strategically boxed in. This is why the strait is not merely a transit route but a strategic fulcrum. Stability here determines whether the First Island Chain holds as a barrier or fractures under pressure.

https://indopacificreport.com/south-china-sea_-a-tinderbox/

The Philippines and the Bashi Channel form the southern gateway of the chain, and their importance has surged in recent years. The Bashi Channel is one of the few deep-water passages connecting the Pacific Ocean to the South China Sea, making it indispensable for both commercial shipping and naval operations. Philippine territory, sitting astride this corridor, offers unmatched positional advantage for monitoring, deterrence, and rapid response. Access agreements and infrastructure development here quietly reshape operational realities without the drama of formal alliances.

The strategic value of these nodes is ultimately about freedom of navigation in one of the busiest maritime corridors on Earth. Energy flows, container shipping, and critical supply chains pass through waters bordered by the First Island Chain every day. Japan’s Ryukyu Islands and Taiwan, in particular, function as natural barriers that limit the outward expansion of rival naval forces, reinforcing denial by geography itself. In this environment, maps are not neutral, they are instruments of power.

US deploys Typhon missile launchers to new location in Philippines

Military and Defense Enhancements

What makes the First Island Chain strategy credible is not rhetoric, but hardware, positioning, and repetition. Under the Pacific Deterrence Initiative, Washington has quietly poured more than $40 billion since 2021 into infrastructure hardening, dispersal, and forward capabilities across the Indo-Pacific. This is not about building giant Cold War–style bases; it is about making forces harder to find, harder to hit, and harder to neutralize in the opening hours of a crisis. The deployment of systems like the Typhon mid-range missile platform and NMESIS anti-ship launchers across Japan and the Philippines reflects this shift, mobile, survivable, and designed explicitly to deny maritime access rather than seek dominance far from home waters.https://indopacificreport.com/south-china-sea_-a-tinderbox/

Equally important is how these capabilities are woven together with allies. Exercises such as Balikatan 2025, involving roughly 9,000 U.S. troops, 5,000 Filipino personnel, and Australian forces, are not symbolic rehearsals. They are operational stress tests for interoperability, command integration, and real-time coordination under contested conditions. Layered onto this is the rapid adoption of emerging technologies, long-range precision strike, cyber resilience, and AI-enabled intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance. Together, they form a distributed deterrence network that complicates adversary planning across every domain, not just at sea.

Deterrence and Signaling

The Pentagon’s message along the First Island Chain is subtle by design. This is not deterrence through spectacle, but deterrence through persuasion. Forward deployments, rotational forces, and routine exercises are calibrated to project resolve without triggering crisis dynamics. The emphasis is not on sudden surges, but on steady, predictable presence that normalizes preparedness rather than dramatizing it.

This is where the “silent signal” becomes powerful. Each missile deployment, access agreement, and joint drill quietly reinforces the same conclusion: the region is not undefended, alliances are not hollow, and coercion will be contested from day one. For adversaries, the psychological effect is cumulative. For partners, it is reassuring. The signal is clear without being provocative, capability is in place, coordination is real, and escalation is neither necessary nor attractive.

https://indopacificreport.com/should-taiwan-expose-beijings-airspace-and-eez-violations-like-the-philippines-does-in-the-south-china-sea/

Regional Security Implications

For China, the First Island Chain remains a strategic constraint that shapes every major contingency plan. Beijing’s heavy investment in anti-access and area-denial capabilities is itself an admission of how seriously this barrier is taken. The chain complicates power projection, stretches logistics, and undermines assumptions about rapid, decisive operations in the near seas. In short, it forces harder choices and longer timelines, both enemies of coercive strategy.

Beyond China, the regional picture is more complex. North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs still influence force posture decisions, but increasingly as a secondary consideration rather than the organizing principle of U.S. strategy. The broader effect of the First Island Chain is alliance deepening. Japan, the Philippines, Australia, and other partners are no longer peripheral contributors; they are integrated nodes in a collective deterrence architecture that distributes both risk and responsibility.

Economic and Diplomatic Dimensions

Security along the First Island Chain is inseparable from economics. The same waters that host naval patrols also carry energy shipments, container traffic, and the arteries of the global semiconductor supply chain. Any instability here would not stay regional, it would cascade into inflation, supply shocks, and industrial disruption worldwide. This is why deterrence in the Western Pacific is as much about economic stability as military balance.

Diplomatically, the strategy walks a careful line. Military deterrence is paired with constant engagement, nudging allies toward higher defense spending, greater interoperability, and shared strategic assumptions. Multilateral frameworks such as ASEAN, the Quad, and AUKUS draw much of their practical relevance from this underlying security logic, reinforcing norms of open seas and resistance to coercion without forcing states into binary choices.

Challenges and Criticisms

Still, the approach is not without strain. Sustaining a robust, dispersed posture across a vast maritime theater taxes logistics, budgets, and personnel. High-visibility deployments and frequent exercises also carry the risk of miscalculation, particularly in an environment where every movement is scrutinized and sometimes misread. Critics argue that the strategy risks overextension, locking the United States into commitments that may be difficult to sustain politically or financially over the long term.https://youtu.be/iTN23W9ehOw?si=m0A1G41Z5Xs5B-J3

There is also an ongoing debate about balance. Some warn that an emphasis on military denial could crowd out diplomatic creativity, reducing space for conflict management mechanisms. The challenge is not whether deterrence is necessary, it is how to keep it stabilizing rather than self-reinforcing.

Conclusion and Strategic Outlook

Taken as a whole, the First Island Chain strategy represents a mature evolution in deterrence thinking. It blends geography, technology, and alliances into a posture designed not to win wars, but to prevent them by making aggression untenable. Denial capabilities, integrated with credible partnerships, form the quiet scaffolding of regional stability.

Looking ahead, success will depend on adaptation. Hybrid threats, asymmetric tactics, and rapid technological change will test the resilience of this approach. Yet the long-term importance is unmistakable. Sustaining the First Island Chain is not just about U.S. power projection, it is about preserving an Indo-Pacific order where no single actor can dominate by force, and where readiness and restraint.

https://youtu.be/XkvEyrOkaqg?si=9LiPPk6-L3e-0-Xg