5 Major Issues Haunting the South China Sea in 2026?

In the summer of 1914, Europe did not slide into war because its leaders sought one. It drifted there through routines that appeared manageable—mobilisations described as defensive, alliances justified as precautionary, and incidents absorbed repeatedly until they no longer could be. By the time the crisis was recognised for what it was, momentum had already taken over.

By 2026, the South China Sea carries an uncomfortably similar dynamic.

What defines the region by 2026 is not a single decisive confrontation, but the steady accumulation of pressure: violent maritime encounters that no longer shock, quiet shifts in control that harden with time, and an expanding web of alliances that increasingly ties local disputes to global rivalries. Collisions, boardings, blockades, administrative claims, and missile deployments have become part of the baseline, rather than exceptions demanding restraint.

Let us examine five interlocking developments shaping the South China Sea, each grounded in incidents from 2024 and 2025 and each reinforcing the others. Taken together, they explain why the region has grown more volatile even in the absence of open war—and why managing the next crisis is likely to be harder than managing the last.

If history offers a warning, it is a simple one. Conflicts rarely begin when red lines are crossed. They begin when red lines fade, quietly and incrementally, until no one is quite sure where they ever were.

That process is already under way—beginning with the steady lowering of the threshold for armed conflict.

1) Lowering the Threshold for Armed Conflict

The South China Sea is becoming more dangerous—not because any state wants a war, but because the quiet understandings that once kept violence contained are beginning to fade. What we are watching is not escalation by design, but erosion by habit. As governments redefine what might constitute an act of war while allowing increasingly rough encounters to continue at sea, the region is drifting into a space where a single death could suddenly trigger something far larger.

For years, escalation control rested on an unspoken bargain. States absorbed losses, softened their language, and worked carefully to keep incidents below the point where retaliation became unavoidable. Ambiguity did much of the work. It still does—but far less effectively than before. The buffer remains, but it is thinner, and it is under strain.

The most important shift came not from Beijing, but from Manila. In 2024, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. publicly stated that the deliberate killing of a Filipino in disputed waters would be “close to an act of war.” The intent was deterrence. The consequence was more complex. By defining a trigger so explicitly, Manila narrowed its own room for maneuver and transferred strategic pressure downward, onto commanders operating at sea who now know that a single fatality could force political escalation.

That risk became real almost immediately.https://indopacificreport.com/china-demands-philippines-stop-us-japan-military-cooperation/

On June 17, 2024, what should have been a routine Philippine resupply mission to Second Thomas Shoal escalated into the most violent confrontation yet between Philippine and Chinese forces. At least eight Filipino personnel were injured, one losing a thumb. Philippine officials reported that Chinese personnel boarded government vessels, seized weapons and equipment, and used bladed tools to disable inflatable boats. Most significantly, this marked the first known instance of Chinese forces boarding a Philippine state vessel at this contested feature.

This was not another episode of water cannons or close maneuvering. A line was crossed. Physical contact led to serious injury, and the encounter demonstrated how quickly routine pressure tactics can tip into something far more dangerous.

Second Thomas Shoal has always been uniquely sensitive because it is Manila’s most exposed red line. The Philippines maintains its claim through the grounded BRP Sierra Madre, a rusting World War II–era ship intentionally beached in 1999. A small detachment of marines lives aboard, entirely dependent on periodic resupply missions. Those missions are predictable, visible, and easy to intercept.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b-JKvywAi-M

Since 2023, Chinese forces have steadily raised the pressure—moving from blocking and water cannons to ramming, swarming, and now boarding actions. The June 2024 incident showed how quickly incremental escalation can collapse into high-stakes violence, even without a shot being fired.

What makes this moment particularly dangerous is how sharply it diverges from earlier crisis-management practices. During the deadly 2020 clash between China and India in the Galwan Valley, both sides worked deliberately to contain escalation. Firearms were avoided, official statements were restrained, and casualty figures were released slowly. By contrast, Manila has emphasized transparency, public attribution, and alliance signaling. That approach builds legitimacy and international support—but it also leaves far less space to quietly defuse a crisis once emotions harden.

The effects are already visible at sea. Commanders now operate under compressed decision timelines, aware that restraint may carry political costs after red lines have been declared. Rules of engagement harden as even non-lethal encounters take on strategic meaning. Political leaders, meanwhile, find it harder to step back without appearing to retreat, because public commitments have boxed them in.

Why resupply mission to Sierra Madre in South China Sea generates controversy?

In practice, deterrence messaging has slipped from the strategic level down to the tactical frontline—precisely where miscalculation is most likely.

There are still ways to slow this drift. Public language can be recalibrated, keeping deterrence firm while restoring enough ambiguity to absorb shocks. Clear incident-prevention mechanisms—limits on boarding, minimum distances, use-of-force standards—can reduce the chance that encounters turn violent. Permanent crisis backchannels between militaries and coast guards can help drain heat from fast-moving situations before they erupt in public.

2) Normalisation of High-Risk Encounters: The Perilous New Normal

What is striking about the South China Sea today is not a single dramatic crisis, but how easily danger has become routine. Actions that once would have triggered urgent calls between capitals—ramming, water cannons, aggressive shadowing, even extended blockades—are now treated as part of everyday operations. Risk is no longer an exception to be managed. It has become part of the system itself.

This shift is driven less by deliberate escalation than by sheer congestion. The South China Sea is now one of the most crowded and militarised maritime spaces in the world. Around seventy occupied features and more than ninety military or coast guard outposts are scattered across the region. Each one generates patrols, resupply runs, and enforcement missions. Add maritime militia fleets, national navies, coast guards, and a growing presence of allied vessels, and the sea begins to resemble a permanent traffic jam—except every ship is armed, alert, and operating under a different set of assumptions.https://youtu.be/Z02Qq1A1GJo?si=1FC448tXIVC1vvrq

The result has been a steady stream of close calls. Footage and official reports from 2024 and 2025 show repeated water-cannon incidents, deliberate ramming, and manoeuvres carried out at distances where error is almost inevitable. This is no longer a theoretical risk. In August 2025, a Chinese coast guard cutter and a PLA Navy destroyer collided near Scarborough Shoal while operating close to Philippine vessels. The coast guard ship was damaged, and the incident briefly revealed an uncomfortable reality: even forces nominally on the same side can lose control when pressure, crowding, and tempo converge.

China-Philippines Confrontations in the South China Sea on Second Thomas Shoal

Sabina Shoal illustrates how this new normal takes hold in practice. In 2024, the low-tide feature became the focus of a prolonged standoff after the Philippines deployed one of its most capable coast guard vessels, BRP Teresa Magbanua, to maintain a presence. China’s response was not a single dramatic move, but sustained pressure—constant shadowing, tight manoeuvres, and repeated interference that disrupted resupply. Over time, the strain accumulated. Supplies dwindled, fatigue set in, and the Philippine ship was eventually withdrawn and replaced. No shots were fired, yet the balance on the water shifted all the same.

What makes this pattern especially dangerous is that it no longer feels temporary. Crews on all sides are adapting to an environment where aggressive contact is expected rather than avoided. Large-scale exercises involving the United States and its partners add yet another layer of complexity, placing more ships and aircraft into already congested spaces. With each additional actor, the chances increase that a routine intercept becomes a collision, or that a poorly judged manoeuvre is interpreted as a deliberate provocation.

From an operational standpoint, the logic is straightforward. More vessels, tighter operating areas, longer deployments, and higher political stakes mean that accidents cease to be rare anomalies and begin to look like statistical outcomes. A snapped tow line, a momentary steering failure, or a misjudged turn during a swarm can escalate faster than diplomats can respond—especially when the incident is captured on video and narratives harden almost immediately.

This drift can still be slowed, but only if safety is treated as a strategic priority rather than a technical afterthought. Clearer communication channels, agreed minimum passing distances, and better real-time information sharing would reduce the risk of miscalculation. Formal mechanisms for reporting and reviewing near-misses could also make dangerous behaviour harder to dismiss as routine.

3) Collapse of red lines and irreversible “facts on the water”

If the South China Sea ever had clear red lines, they are now badly eroded. What has replaced them is not a sudden land grab or a dramatic military confrontation, but something quieter and far more durable. Control is being constructed through routine—through paperwork, patrol schedules, and physical presence. Legal designations are layered onto steady enforcement, and over time that combination turns contested space into something that appears administered, often without a single shot being fired.

Beijing has refined this approach by fusing bureaucracy with constant activity on the water. The clearest illustration came in September 2025, when China formally designated Scarborough Shoal as a national marine nature reserve. On paper, it was an environmental measure. In practice, it rested on more than a decade of near-continuous coast guard patrols that have largely excluded Philippine vessels since 2012. Manila protested, as expected. But the designation still mattered. It quietly shifted Scarborough from a disputed feature toward something that looks—and increasingly functions—like governed territory.

This is the power of administrative moves. They reverse the burden of action. Once an area is wrapped in domestic law and reinforced by regular enforcement, challenging it no longer feels like defending the status quo. It begins to look like dismantling an established arrangement. Politically, that is a much harder case to make, both domestically and internationally.

The same pattern is emerging elsewhere. Around Sandy Cay and near Thitu Island—known in the Philippines as Pagasa—Chinese maritime militia, coast guard, and naval vessels have been operating ever closer to Philippine-held features, sometimes within only a few nautical miles. These are not isolated incidents or brief spikes in tension. They form part of a steady squeeze: persistent proximity, interference with resupply, and subtle limits on movement. No single moment appears decisive, but taken together they steadily narrow Manila’s room to operate.

Scarborough Shoal remains the clearest case because it shows how law and enforcement reinforce each other over time. Once the reserve designation was in place, coast guard patrols could be presented as environmental policing. Philippine fishing activity, in turn, could be labelled illegal. Even if the designation were challenged through legal channels, enforcement on the water would continue in the meantime, further entrenching the arrangement. In this context, time works decisively in favour of whoever is already present.

From an operational perspective, this is what makes administrative consolidation both effective and dangerous. Once a designation is announced and backed by constant presence, reversing it without force becomes politically costly. Push back too hard and you risk escalation. Do nothing and the new reality hardens. Control becomes sticky—not because it is accepted, but because contesting it grows more expensive with each passing month.

https://youtu.be/vmb0B9RBlnA?si=wrFImoURjvlhV0CU

The broader lesson is an uncomfortable one. Incrementalism works. Slow, bureaucratic steps, when paired with steady enforcement, can achieve outcomes that overt militarisation often cannot. For smaller claimants, this creates a harsh dilemma: respond forcefully and risk a crisis you may not be able to manage, or respond cautiously and watch losses become normalized.

There are still options short of confrontation. Multilateral legal strategies—through ASEAN diplomacy or carefully calibrated use of UNCLOS mechanisms—can prevent disputes from being quietly bilateralised. Pragmatic confidence-building measures, such as limited joint fisheries or resource management arrangements, can also complicate consolidation without immediately raising tensions.

4) Alliance militarisation & strategic entanglement (Philippines as a forward hub)

Few developments in the South China Sea have mattered as much—or carried as many trade-offs—as the Philippines’ rapid evolution into a forward hub for U.S. and allied forces. What began as an effort to restore deterrence after years of neglect has, by 2026, drawn Manila deeper into great-power rivalry than at any point since the Cold War. On paper, the country is more secure. In reality, every regional crisis now comes with higher stakes.

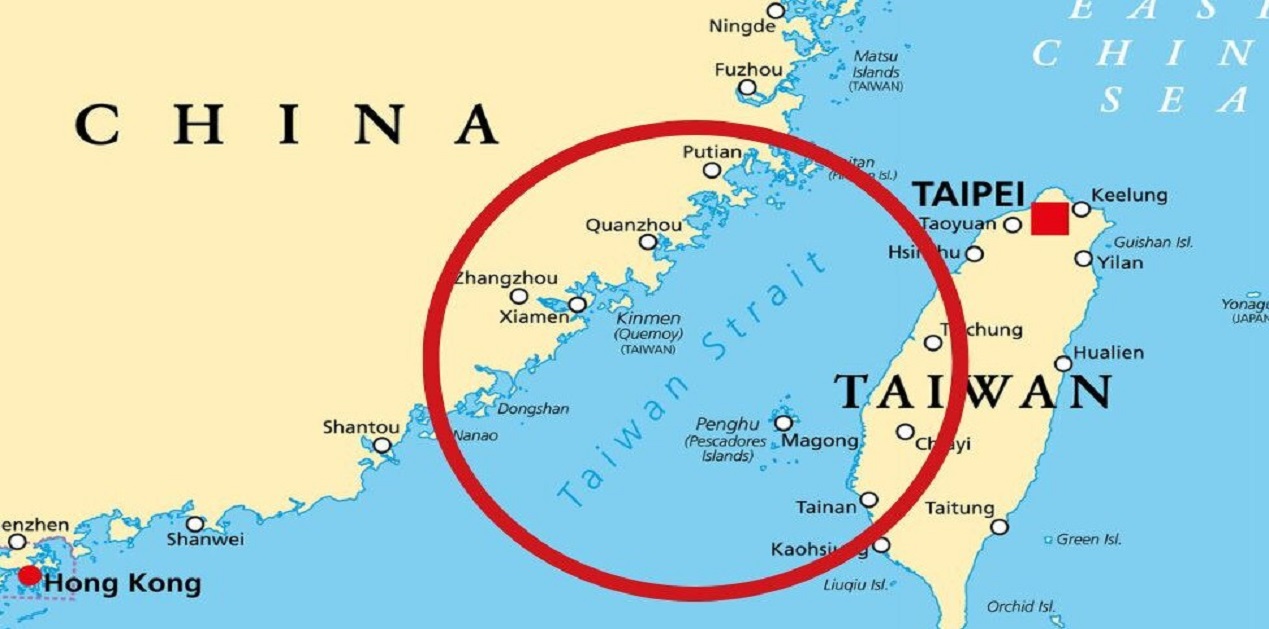

Geography sits at the center of this shift. Northern Luzon overlooks the Luzon Strait, the narrow passage linking the South China Sea to the Taiwan Strait. It has always been strategic ground. Today, it is central to regional war planning. By 2025, U.S. mid-range missile systems, including the Typhon launcher, remained in northern Luzon following joint exercises. Philippine officials described the deployment as temporary and defensive, intended to improve readiness and interoperability. Beijing saw it differently. From China’s perspective, those systems place not just the South China Sea, but parts of the Taiwan Strait—and even sections of the mainland—within potential reach.

This perception has been reinforced by a growing network of security agreements. A Reciprocal Access Agreement with Japan entered into force in late 2025, opening the door to regular Japanese training and deployments on Philippine territory. Expanded defence arrangements with Canada, New Zealand, and Australia followed, along with a sharp increase in joint air and maritime exercises. The effects are increasingly visible at sea: more allied vessels, tighter coordination, and a higher operational tempo in contested waters.

The Typhon deployment captures the dilemma neatly. Militarily, it complicates Chinese planning by introducing uncertainty into any crisis scenario. Politically, it strengthens the belief in Beijing that the Philippines is no longer simply a claimant state defending its own waters, but a critical node in a broader containment strategy. The maps circulating in defence circles make the point clearly: from northern Luzon, major sea lanes, chokepoints, and strategic targets fall within overlapping strike ranges.

That belief carries consequences. Bases hosting allied forces and equipment acquire strategic weight—and with it, strategic risk. In a serious confrontation, particularly one tied to Taiwan, those sites could become priority targets. Even if Manila insists it has no intention of being drawn into a cross-strait conflict, geography and infrastructure may make neutrality difficult once escalation begins.

Operationally, the trade-offs are uncomfortable. A stronger allied presence does enhance deterrence against coercion in the South China Sea. But it also compresses decision timelines and blurs the line between local incidents and regional war planning. A clash near a Philippine-held reef no longer exists in isolation; it is immediately viewed through the lens of U.S.–China rivalry, missile deployments, and alliance signalling. That leaves far less margin for error.

There is also a quieter, longer-term risk: dependency. As allied intelligence, surveillance, and strike assets play a larger role, the Philippines’ own capabilities risk being overshadowed. In a crisis, heavy reliance on external systems could limit Manila’s freedom to decide how far to escalate—or how quickly to pull back.

5) Dangerous Linkage to the Taiwan Strait and the Risk of Cross-Theatre Escalation

One of the most important changes in the South China Sea has little to do with ships or reefs. It has to do with context. By 2026, the region no longer functions as a self-contained arena. Its security dynamics are now tightly bound to the Taiwan Strait, to the point where trouble in one almost automatically reverberates in the other. What were once parallel flashpoints are now overlapping ones, connected by geography, force posture, and the way major powers plan for conflict.

Geography provides the starting point, but politics and deployments have done the rest. Northern Luzon sits at the hinge between the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait, and recent U.S.–Philippine defense cooperation has turned that hinge into an active strategic node. Expanded access agreements, rotational forces, and the presence of longer-range missile systems mean that assets intended for one scenario inevitably shape calculations about the other. From Beijing’s perspective, Philippine decisions—hosting allied forces, expanding exercises, opening bases—are no longer seen as limited to maritime disputes. They are increasingly folded into a broader story about Taiwan.

That framing matters. Chinese official statements and military signaling have repeatedly linked Philippine cooperation with the United States to what Beijing describes as interference in its core interests. The practical effect is that even routine incidents now carry extra strategic weight. A patrol near a contested reef is no longer just about maritime claims; it is interpreted against the backdrop of cross-strait tensions, alliance commitments, and strike ranges. Local encounters begin to feel global.

Military planners have already adjusted to this reality. Across the region, scenario-building increasingly assumes that a crisis over Taiwan would not remain neatly contained. In many models, pressure in the Taiwan Strait is paired with coercive actions in the South China Sea—harassment of rival claimants, disruption of resupply missions, or selective interference with key sea lanes. The logic is straightforward: stretch opponents, overload decision-makers, and force them to manage multiple crises at once. The implication is sobering. A Taiwan emergency would almost certainly heat up the South China Sea, not freeze it.

The risks of this spillover are not abstract. In August 2025, during a tense encounter near Scarborough Shoal, two Chinese vessels—a coast guard cutter and a PLA Navy destroyer—collided while maneuvering aggressively around Philippine patrols. Both ships were damaged, briefly exposing how much strain crews were operating under. The timing was telling. The incident occurred amid heightened U.S.–China friction over Taiwan-related messaging and exercises, a reminder that pressure in one theater can directly shape behavior in another.

The deeper danger is not escalation alone, but confusion. When theaters blur, escalation ladders blur with them. Incidents that might once have been managed locally are now read as moves in a much larger strategic contest. Responses become harder to calibrate, signals noisier, and the risk of misreading intent rises quickly. Crisis management, already difficult in a single flashpoint, becomes far more fragile when several are active at the same time.

For the Philippines, this creates a particularly exposed position. Even without any desire to be drawn into a Taiwan conflict, geography and alliance ties mean that escalation elsewhere could reach Philippine waters rapidly. The same bases, ports, and sea lanes that support deterrence in the South China Sea would immediately matter in a cross-strait scenario, leaving Manila little room to keep crises neatly compartmentalized.

Reducing this risk begins with acknowledging the linkage rather than wishing it away. Cross-theater communication—between militaries and coast guards operating in both the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea—needs to be routine, not improvised. Deconfliction arrangements must account explicitly for spillover, not just isolated incidents. Beyond that, narrowly defined understandings to protect critical sea lanes, civilian shipping, and fisheries during periods of tension could help prevent economic and humanitarian disruptions from becoming accelerants of conflict.

The deeper reality is that escalation is no longer linear. In today’s Indo-Pacific, pressure applied in one place rarely stays there; it ripples outward. The South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait are no longer separate chapters in Asia’s security story. They are part of the same narrative, and it is becoming harder each year to read one without the other.https://youtu.be/3mjgH4UM1Hc?si=Sjbkaq2I2D4wUAYN