South China Sea skirmishes 2025 between China and the littoral states, month by month

How do you measure conflict when no one fires a shot? When the weapons are water cannons, the distances are counted in meters, and the victims are fishermen, scientists, and patrol crews just doing their jobs? That was the reality of the South China Sea skirmishes 2025.

From January to December, the year unfolded as a rolling campaign of pressure.

January opened with “monster ships” and blocked surveys;

February pushed confrontation into the air with dangerous intercepts.

March tested resolve through constant monitoring at outposts;

April fused drills, carriers, and symbolic landings;

May escalated to water cannons against research vessels;

June normalized patrol politics with physical contact.

July tightened control through combat-readiness patrols and stalled diplomacy;

August peaked with collisions and great-power signaling.

September blended lawfare with water cannon at Scarborough;

October mixed symbolism with ramming;

November entrenched coercion as routine, and December ended with injured fishermen and warning flares. No war was declared, but every month narrowed the margin for error, reminding the region that peace now depends less on treaties than on restraint in every single encounter.

January 2025 — Pressure Without Gunfire

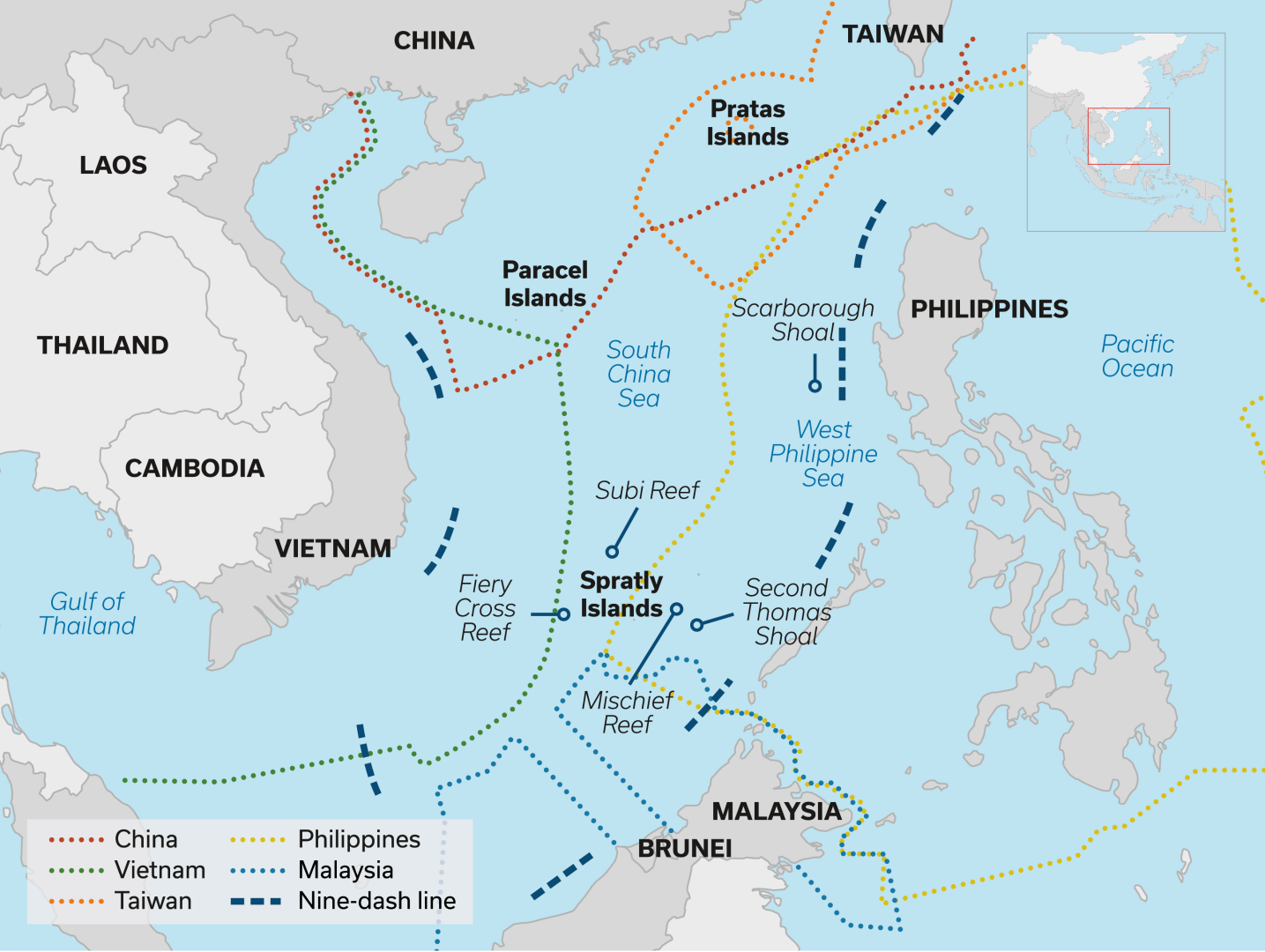

January opened with a calibrated show of force. On January 2, China deployed its largest coast guard cutter, CCG 5901, a 12,000-ton vessel displacing more than many naval frigates, near Scarborough Shoal, well inside the Philippines’ 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The ship’s presence was not fleeting. It was tracked repeatedly by Philippine authorities, signaling endurance rather than transit, and reinforcing concerns in Manila that Beijing was normalizing a constant Chinese law-enforcement presence in contested waters.

By January 11–12, the same cutter was again detected in the area, prompting a direct response from the Philippine Coast Guard, including radio challenges and escort operations. Days later, Manila escalated diplomatically, filing a formal protest that cited both the size of the vessel and its operational behavior as evidence of coercion rather than routine patrols. China, through the China Coast Guard, rejected the accusation, insisting its actions were lawful, highlighting the stark gap between legal interpretations governing the same sea space.

The pressure peaked in the final week of the month. On January 24–25, a Philippine scientific mission near Sandy Cay, close to Thitu Island, was confronted by three Chinese Coast Guard vessels, several small intercept boats, and a PLA Navy helicopter that hovered at dangerously low altitude, forcing the suspension of the survey.

No weapons were used, no hulls collided, and no one was injured but the numbers told their own story: multiple cutters against a civilian research team, heavy platforms against unarmed scientists. January ended with a clear precedent set, maritime pressure in 2025 would be persistent, quantitative, and carefully controlled, yet always one miscalculation away from escalation.

February 2025 — The Air Domain Turns Volatile

February marked a clear escalation above the waves. On February 4, the Philippines and the United States conducted a joint air patrol over Scarborough Shoal, pairing Philippine FA-50 fighter jets with U.S. B-1B bombers, aircraft capable of long-range strike missions exceeding 9,000 km without refueling. For Manila, the patrol was framed as alliance readiness and air-domain awareness. For Beijing, it was a direct challenge over one of the most tightly guarded features in the South China Sea. The signal was unmistakable: deterrence was no longer confined to coast guard hulls, but extended into contested airspace.

That tension sharpened on February 18, when a Chinese navy helicopter flew within just a few meters of a Philippine government aircraft during a patrol near Scarborough, according to the Philippine Coast Guard. Aviation experts widely note that safe separation between aircraft is normally measured in hundreds of meters, not single digits. The close pass dramatically raised collision risk and prompted Manila to announce plans for a diplomatic protest. China rejected the account, accusing the Philippine aircraft of intrusion, an illustration of how air intercepts compress decision-making time and magnify the danger of miscalculation.

The confrontation quickly widened into an alliance signaling. On February 19, Washington publicly condemned the incident, with U.S. Ambassador MaryKay Carlson calling the maneuver dangerous and urging China to comply with international law. Two days later, Beijing countered by claiming it had warned off Philippine aircraft near disputed features in the Spratly Islands, showing how both sides now contest not just waters, but the very definition of “lawful presence” in the sky.

The month closed with a reminder that pressure is regional, not bilateral. On February 24, China announced live-fire exercises in the Gulf of Tonkin shortly after Vietnam published a new maritime baseline, an administrative act under UNCLOS that can affect 200-nautical-mile EEZ calculations. No shots were exchanged between rivals, but the timing spoke volumes. February 2025 showed how the South China Sea contest is expanding vertically and geographically: from ships to aircraft, from Scarborough to the northern approaches, and from isolated incidents to a sustained cycle of signaling, denial, and risk.

March 2025 — Pressure by Presence, Signaling by Patrol

March was defined less by collisions than by control of rhythm. On March 4, a routine Philippine provisions run to Second Thomas Shoal, supplying personnel stationed aboard the grounded BRP Sierra Madre, was publicly “monitored” by the China Coast Guard. The mission itself was modest: a civilian supply boat sustaining a detachment on a rusting ship that has sat on the reef since 1999.

But the stakes were strategic. Second Thomas Shoal lies well within the Philippines’ 200-nautical-mile EEZ, and each successful resupply reinforces Manila’s ability to maintain presence despite constant Chinese shadowing. Beijing’s decision to publicize the monitoring was deliberate, an attempt to cast itself as the de facto regulator without physically stopping the mission.

By the end of the month, the contest had shifted from the shoal to the wider narrative space. On March 28–29, China’s military announced a South China Sea patrol and issued pointed warnings toward Manila, closely timed with renewed U.S.–Philippine alliance messaging. The signal was unmistakable: patrols were no longer just maritime movements, but political statements. Philippines KF-21 Boramae Acquisition

Visibility itself became deterrent, demonstrating that Chinese naval and coast guard forces can surge and posture across contested waters at will, regardless of diplomatic reassurance from Washington.

March 31 closed the month with what analysts described as “patrol politics.” As senior U.S. defense engagement spotlighted Manila, Beijing leaned into a sustained presence rather than a headline-grabbing confrontation. No water cannons. No collisions. Just ships at sea, statements issued, and missions watched. March 2025 showed how the South China Sea struggle increasingly plays out not through dramatic clashes, but through calibrated monitoring, timed patrols, and the steady contest over who sets the rules and the tempo of daily operations.

April 2025 — Coercion Meets Coalition

April marked the densest month of interaction yet, where routine logistics, legal forums, and major military exercises collided in the same operational space. Early in the month, China’s Coast Guard again said it had “questioned and monitored” a Philippine resupply mission to Second Thomas Shoal, where the grounded BRP Sierra Madre has served as Manila’s forward presence since 1999.

The mission involved an unarmed civilian vessel operating well within the Philippines’ 200-nautical-mile EEZ, yet Beijing’s language framed it as an activity requiring oversight, reinforcing a gatekeeper narrative without physically stopping the run.

By mid-April, pressure shifted into both diplomacy and close-quarters maneuvering. On April 14, Manila raised “dangerous incidents” during ASEAN–China Code of Conduct talks, signaling a deliberate effort to multilateralize what China prefers to keep bilateral. A day later near Scarborough Shoal, Chinese and Philippine vessels accused each other of unsafe blocking maneuvers at close range, tactics that typically occur at distances of tens of meters, where a single steering error can cause collision.

The same reporting cycle also flagged Chinese research activity near Batanes, showing how competition now spans logistics, fisheries, and scientific surveys. How the Philippine Army’s 10th Infantry ‘Agila’ Division Is Rewriting AFP Strategy

The strategic temperature rose sharply with Balikatan 2025, which began on April 21. The exercise involved 14,000+ U.S. and Philippine troops, featuring systems such as HIMARS and NMESIS, capabilities explicitly relevant to maritime denial in the South China Sea. Within days, China responded with high-end signaling: the aircraft carrier Shandong deployed near Philippine waters, a platform capable of generating dozens of fixed-wing sorties per day.

The action-reaction loop tightened further as joint U.S.–Philippine maritime and air operations followed, including air-defense drills that shot down drones, reflecting the growing importance of surveillance and counter-UAS capabilities in contested seas.

April closed with symbolic and narrative confrontation. On April 28, Chinese state media claimed coast guard personnel had landed on Sandy Cay, while the Philippines denied any Chinese presence after its own personnel landed, an episode defined less by occupation than by competing claims of control.

Two days later, China announced another naval patrol as Philippine and U.S. air forces flew a joint mission overhead. April 2025 made one reality unmistakable: the South China Sea contest is no longer episodic. It is continuous, multi-domain, and increasingly shaped by synchronized coercion on one side and visible coalition signaling on the other.

May 2025 — Coercion Spills Beyond the Shoals

May marked a shift from symbolic pressure to physical risk, with South China Sea frictions widening beyond naval outposts to include fisheries, science, and third-party claimants. The month opened with Vietnam lodging formal diplomatic protests over activities around Sandy Cay, reminding all parties that even bilateral-looking incidents ripple across overlapping claims. For Hanoi, such actions are not abstract: precedents set by landings, patrols, or “monitoring” can shape future interpretations of sovereignty and 200-nautical-mile EEZ rights across the Spratlys.

The confrontation turned kinetic on May 21. During a marine scientific research mission near Sandy Cay and the Pag-asa Cays, a China Coast Guard vessel used a high-pressure water cannon and executed a sideswipe maneuver against the Philippine Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources ship BRP Datu Sanday. Water cannons on large coast guard cutters can project streams at several hundred liters per second, powerful enough to damage equipment and injure crew at close range. Manila reported damage and safety risks to civilian personnel, an escalation because the target was a fisheries and research vessel, not a military or resupply ship.

The days that followed exposed the core gray-zone playbook. Beijing said it had imposed “control measures” against Philippine vessels it claimed had entered waters near Subi Reef and Sandy Cay, while Manila rejected the charge outright, insisting its activities were lawful. The terminology mattered. “Control measures” is not just descriptive; it is an assertion of enforcement authority in disputed space, reinforced through both maneuver and messaging.

By May 23, the dispute had escalated into a diplomatic exchange involving Washington, with China warning of a “resolute response” and the United States condemning what it described as dangerous and aggressive actions.

By month’s end, the Philippines drew a firm line on narrative ground. On May 29, Manila rejected China’s objections and reaffirmed that its operations were routine exercises of sovereign rights under international law, not provocations. May 2025 showed how the South China Sea contest is broadening: from reefs to research missions, from bilateral encounters to multilateral reactions, and from quiet monitoring to incidents where civilian safety is directly at stake.

June 2025 — Patrol Politics Turn Physical

June was the month where signaling hardened into contact. It opened with structure and alliance choreography: on June 4, the Philippines and the United States conducted their 7th Maritime Cooperative Activity, operating off Occidental Mindoro and Zambales. While deliberately conducted away from disputed features, the exercise reinforced interoperability, shared maritime domain awareness, and freedom-of-navigation principles. These recurring drills, now held multiple times a year, have become part of the strategic background noise that steadily raises Chinese sensitivity to “normalized” allied presence.

Beijing responded first in words, then in movement. On June 5, China warned the European Union against “provoking trouble” and reiterated criticism of Manila’s reliance on “outside forces.” Days later, on June 14–15, the PLA’s Southern Theater Command announced joint sea-and-air patrols in the South China Sea and issued a direct warning to the Philippines. The pattern was familiar: alliance activity triggers patrol announcements, patrols reinforce deterrence, and official statements frame Manila as the destabilizing factor even as Chinese forces expand their operational footprint across air and sea domains.

Mid-June showed how the competitive field is widening. The Philippines conducted a joint drill with Japan in disputed waters, followed by trilateral coast guard exercises with Japan and the United States held from June 18–20. These drills focused on collision response, fires, and search-and-rescue scenarios highly relevant to South China Sea encounters, where vessels often operate at tens of meters separation. Coast guard cooperation matters precisely because most confrontations occur below the naval threshold, where non-lethal force and maneuvering dominate escalation dynamics.

The month ended where theory met risk. On June 20 near Scarborough Shoal, Chinese Coast Guard vessels used water cannons and aggressive maneuvers against Philippine fisheries missions delivering supplies to Filipino fishermen. One Philippine vessel was struck; another narrowly avoided impact. China said it took “necessary measures” to expel what it called intruding ships.

The exchange followed a now-established template: non-lethal force, competing legal narratives, and a deliberate effort to assert control over access to a vital fishing ground. June 2025 made one thing clear: the South China Sea contest is no longer just about presence. It is about who can sustain pressure, manage escalation, and still operate when signaling turns physical.

July 2025 — Pressure Without Impact

July was quieter on the surface but heavy with intent. On July 3, China’s PLA Southern Theater Command announced “combat readiness” sea-and-air patrols around Scarborough Shoal, reinforcing a posture it said had been ongoing since June. No collision was reported that day, but the label mattered. A declared combat-readiness patrol is signaling, not routine movement, an effort to normalize Chinese control of both air and sea space near a feature just ~220 km from Luzon and central to fisheries access and presence politics.

The month’s other pressure point surfaced diplomatically. At the July 9 ASEAN foreign ministers’ meeting in Kuala Lumpur, the stalled South China Sea Code of Conduct was again identified as a major regional friction. With fewer headline encounters at sea, competition shifted into process warfare: shaping language, delaying constraints, and preserving ambiguity over what counts as lawful enforcement versus coercion. July showed that even when water cannons stay silent, pressure continues, through patrol declarations, legal positioning, and the steady contest over who defines “normal” behavior in contested waters.

August 2025 — Collision and Coalition

August was the most volatile month of 2025 in the South China Sea, marked by coalition expansion, a serious collision, and rapid great-power signaling. It began on August 4 with the first-ever Philippines–India joint naval sail in the West Philippine Sea, conducted inside the Philippines’ 200-nautical-mile EEZ. While no shots were fired, the message was strategic: Manila was widening its security partnerships beyond the United States and Japan. India’s participation mattered because it brought a major Indo-Pacific naval power into waters Beijing treats as politically sensitive, reinforcing the idea that access and navigation are not China–Philippines issues alone.

That signaling turned dangerous on August 11 near Scarborough Shoal. During an aggressive interception of the Philippine Coast Guard vessel BRP Suluan, a PLA Navy destroyer and a China Coast Guard cutter collided with each other, causing visible damage to the coast guard ship. This was unprecedented for 2025: Chinese state vessels were physically damaged during a coercive maneuver, showing how operations conducted at high speed and close quarters, often within tens of meters, can spiral beyond control.

Manila released footage showing its crew evading the pursuit and later offering assistance, while condemning the unsafe conduct. Beijing blamed Philippine “provocation,” illustrating how accountability narratives harden after kinetic risk.

The aftermath unfolded fast. On August 12–13, the United States deployed USS Higgins (DDG-76) and USS Cincinnati (LCS-20) to waters near the shoal, signaling deterrence and support for freedom of navigation. China responded with statements claiming it had “driven away” a U.S. destroyer, classic post-incident narrative defense. The exchange elevated the episode from a China–Philippines confrontation into a broader great-power signaling contest, drawing concern from regional partners including Japan, Australia, and New Zealand. China Fires Flares at Philippines Aircraft as EW Warfare Goes Live in the Spratlys

By late August, Beijing leaned into normalization. China announced expanded and routine coast guard patrols around disputed atolls, including Scarborough, explicitly linking them to safeguarding sovereignty and maritime rights. The emphasis was telling: even after one of the year’s most dangerous incidents, the strategic answer was not restraint, but sustained presence. August 2025 showed the South China Sea at its most exposed, where coalition building, coercive tactics, and operational risk converged, and where a single misjudgment proved capable of damaging ships, reputations, and regional stability at once.

September 2025 — Lawfare and Water Cannon

September was one of 2025’s most volatile months in the South China Sea, centered on Scarborough Shoal. China moved first with lawfare, announcing plans to designate the shoal a national marine nature reserve, an environmental label widely seen by Manila as an attempt to formalize control over a feature inside the Philippines’ 200-nautical-mile EEZ. The proposal drew immediate Philippine protest and U.S. warnings against unilateral changes to the status quo.

Days later, Beijing issued a military warning accusing the Philippines of provocation and cautioning against cooperation with “external forces,” pairing diplomatic pressure with implied force. The tension turned kinetic on September 16, when the China Coast Guard used water cannons against Philippine vessels near the shoal. China claimed intrusion by more than ten ships; Manila said its vessels were conducting lawful fisheries and support activities and were aggressively harassed. The episode highlighted a clear escalation: legal claims, narrative control, and non-lethal force converging at one of the region’s most dangerous flashpoints.

October 2025 — Symbols, Ramming, and Alliance Lines

October blended symbolism with sharp contact. China’s coast guard staged a National Day flag-raising near Scarborough Shoal, a quiet but pointed act of presence politics meant to normalize control. Days later, China and Malaysia announced joint drills, showing Beijing’s effort to complicate coalition dynamics within ASEAN.

The month turned kinetic on October 12, when the China Coast Guard used water cannon and rammed a Philippine fisheries vessel near Thitu Island, one of the most dangerous encounters of the quarter. Washington publicly condemned the incident, reinforcing the now-familiar ladder: unsafe contact → attribution → alliance signaling.

November 2025 — Coercion by Routine

November lacked spectacle but not pressure. China intensified continuous patrols around Scarborough, shifting from episodic clashes to the normalization of enforcement. Philippine vessels reported aggressive shadowing and near-collisions, tactics designed to intimidate without triggering crisis thresholds. Diplomatically, the South China Sea dominated APEC sidelines and ASEAN consultations, while Manila filed fresh protests to document behavior. The message was subtle but firm: control through persistence, not headlines.

December 2025 — Civilians in the Crosshairs

December brought risk back into focus. Early in the month, Chinese forces fired warning flares at a Philippine patrol plane, then claimed to have expelled Philippine aircraft and vessels near disputed features. The most serious episode followed on December 13–14, when water cannons and blocking maneuvers injured Filipino fishermen near Sabina Shoal, damaging boats and cutting anchor lines. Manila announced a formal protest; the United States condemned the actions; Beijing denied wrongdoing. Non-lethal force again proved capable of causing real harm.

2025 — What the Year Really Showed

By year’s end, the South China Sea had not erupted into war, but it had hardened. Patrols became permanent, water cannons routine, lawfare explicit, and alliances more visible. Civilians, scientists, and fishermen were pulled into the front line. Peace held, but only just. In 2025, stability was no longer the absence of conflict; it was the careful management of constant confrontation, one close encounter at a time.

Subic Bay Returns to the Geopolitical Spotlight US–China Rivalry in the Indo‑Pacific